In today’s complex world of commerce, the products that we buy are often assembled from parts and materials that originate from around the globe. Until recently, we could take this complexity for granted because everything worked smoothly. As anyone who tried to buy toilet paper during the height of the pandemic knows, that hasn’t always been the case over the last 18 months.

The cost and availability of raw materials, energy, and labor talent vary widely within and across countries. Global supply chains link these inputs efficiently and allow U.S. businesses to produce high quality products at prices that are competitive both domestically and internationally. Indeed, a well-managed supply chain makes businesses more competitive, expands their market reach, and reduces costs.

But new challenges are creeping in, especially as we recover from COVID. Anyone that has shopped for a car recently knows that semiconductor shortages are having a very real impact on availability. Semiconductors help control everything from airbags to brakes to rear view cameras—and the shortages in semiconductors are leading to inventory shortages and markedly higher auto prices. Depending on the product, other growing risks include geopolitical instability, natural disasters, trade wars, cyber attacks or simple port congestion due to ever-shifting supply and demand dynamics.

Recent years have brought these risks into sharp focus, highlighting the need for resiliency, as well as efficiency. COVID-19 has locked down economies, choking off downstream entities in the supply chain and revealing the limitations of “just in time” manufacturing strategies, and those posed by cyber incidents such as the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack. Many critical minerals, whose mining or refining is often dominated by one or two countries, have seen price spikes and rationed distribution. For example, according to reports from Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, the price for battery grade-lithium went up 88% from the start of 2021 through mid-March.

Geopolitical incidents, including the 2010 maritime dispute between Japan and China, led to China banning the export of critical minerals to Japan and significant increases in the prices of critical minerals, and natural disasters such as the 2011 Fukushima earthquake had rippling effects for lithium batteries and semiconductors that forced some companies in Japan to stop production, underscoring the risks posed to fragile supply chains. Clearly, supply chain weaknesses—both domestic and international—present an obvious threat to our economic and national security.

So how does this relate to energy and climate change? Increasingly, the world’s growing focus on mitigating greenhouse gas emissions by expanding access to clean energy technologies is exposing new supply chain challenges. For example, many of the technologies to reduce emissions—like solar panels, electric cars, and wind turbines require a steady supply of critical minerals, semiconductors, and batteries. Further, as these efforts to decarbonize our economy grow, there will be an enormous surge in demand. A robust supply chain that provides for ready access to these products is thus essential for achieving climate goals.

Recognizing this importance, in February President Biden signed an Executive Order directing a 100-day government-wide assessment of both specific and sectoral supply chain vulnerabilities. The 250-page White House report, reviews four critical products supply chains: semiconductor manufacturing and advanced packaging; large capacity batteries; critical minerals and materials and pharmaceuticals and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). It was accompanied by a DOE-led National Blueprint for Lithium Batteries that details a number of specific steps the Administration plans to take to address concerns regarding sourcing and manufacturing related to electric vehicles.

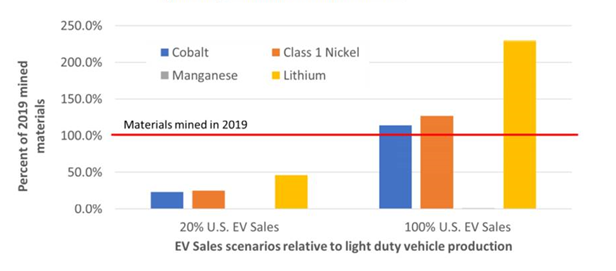

Two charts from the Blueprint are useful for illustrating the risks our supply chains face in meeting future challenges. The first considers the adequacy of global supply of four materials—cobalt, manganese, nickel, and lithium—and compares this to the demand that would be created by U.S. light-duty vehicles if 20% or 100% of sales were EVs. As shown below, if U.S. sales were all EVs, those vehicles alone would require more than current world mining output for all uses of cobalt, nickel, and lithium. That’s simply enormous demand growth, and it doesn’t even consider the concurrent EV-related demand growth occurring in Europe, Asia and elsewhere.

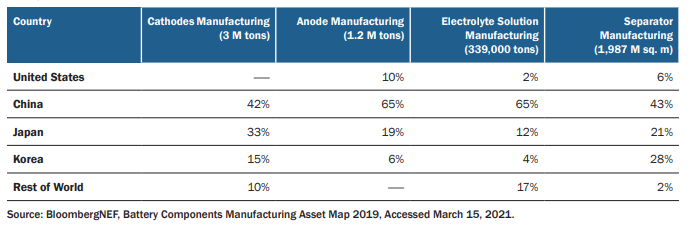

A second chart examines lithium-ion battery manufacturing, and the percentage of total manufacturing capacity for various components in key countries. At each stage of manufacturing, the U.S. share of capacity is tiny, and China is dominant, which presents a risk to meeting climate goals, in addition to presenting a significant and growing threat to energy and national security.

With this assortment of concerning vulnerabilities well-established, these reports identify a broad suite of government actions and policy recommendations aimed at shoring up key supply chains. The White House report indicates its intent to employ a broad range of tools, “including ally and friend-shoring, and stockpiling, along with investments in sustainable domestic production and processing will all be necessary to strengthen resilience.” With respect specifically to the electric vehicle battery supply chain, the Biden Administration calls for “an ecosystem-building approach that includes supporting domestic demand, investing in domestic production, recycling and R&D, and targeting support of the U.S. automotive workforce.”

Specific strategies underlying this approach include identifying potential U.S. production and processing locations for critical minerals, increasing tax incentives and financing mechanisms across the full battery supply chain, and using the federal government’s purchasing power to procure batteries and incentivize greater private investment. The Chamber welcomes this comprehensive set of actions, which generally align with our formal comments provided to the Department of Energy and Department of Defense at the outset of this effort.

However, the Biden Administration appears to be sending mixed signals on a critical early step in EV battery supply chains: domestic mining. While its report calls for domestic extraction of lithium and identifying opportunities to potentially expand cobalt mining, it appears to favor doing so as more of a last resort, stating that increased domestic production should be considered “where demand can’t be met through alternative means and secondary sources.”

Equally concerning is the administration’s call for expanded regulatory constraints on domestic mining. While the Chamber and many others have emphasized that the administration’s efforts to accelerate the clean energy transition must be accompanied by permit streamlining in order to attract increased mining investment and production, the supply chain report recommends the opposite. Specifically, it recommends that Congress expand regulations governing mining on public lands, with greater EPA involvement in permitting mines and that an interagency team identify additional regulatory actions that should be undertaken before mining begins.

This is especially disappointing because the report does not explain what, if any, shortcomings exist in the already extensive and time-consuming permitting process. We should of course ensure that environmental standards remain paramount, but instituting new regulatory and permitting obstacles sends a conflicting message to metals mining and refining businesses poised to help address the critical minerals security concerns that everyone agrees on.

Our supply chain risk and vulnerabilities have developed over many years and won’t be cured overnight. But the good news is that there is a strong consensus that securing a reliable supply of critical minerals and materials is necessary to not only meet national and global climate goals, but also maintain America’s energy security in the decades ahead. There is no one-size-fits-all solution, so flexible, pragmatic, and balanced approaches will be necessary to achieve to achieve these shared goals. The Chamber looks forward to continuing its engagement as the Biden Administration executes these plans and continues its broader review over the months ahead.