On Fox News Sunday yesterday, Reince Priebus, President-elect Donald Trump’s pick for White House Chief of Staff, summed up pretty well the huge challenges Rex Tillerson, the President-elect’s choice for Secretary of State, faced as CEO of ExxonMobil:

“The Good Lord didn't put oil in all freedom, democracy-loving countries. As being an executive of ExxonMobil, he had to go there and have these relationships.”

This point about most of the world’s oil being produced in countries that aren’t free is one we made in the latest edition of our Index of U.S. Energy Security Risk. A special section of the just-released report takes a deeper dive into the security of world crude oil supplies and examines the amount of crude oil being produced in countries Freedom House, the well-respected human rights watchdog, categorizes as “Free,” “Partly Free,” and “Not Free.” Examples of Free countries include the United States and Canada, Partly Free countries include Nigeria and Pakistan, and Not Free countries include China and Saudi Arabia. (More on how these categories are determined can be found at the Freedom House website here.)

We chose these measures of political and civil liberties as a proxy for reliability. Our reasoning is that countries exhibiting a greater degree of political and civil liberties are more likely to be politically stable and reliable trading partners and are less likely to join cartels or use oil supplies to achieve geopolitical aims. The turmoil over the past few years in places like Algeria, Iraq, Iran, Libya, and Nigeria and other oil-producing countries with limited freedoms confirms the link between freedoms and political stability. Many members of Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries cartel also score poorly in Freedom House’s classification.

If all of the world’s oil was produced in democracies, oil imports would be primarily a balance of trade issue, not a national security issue. But it isn’t.

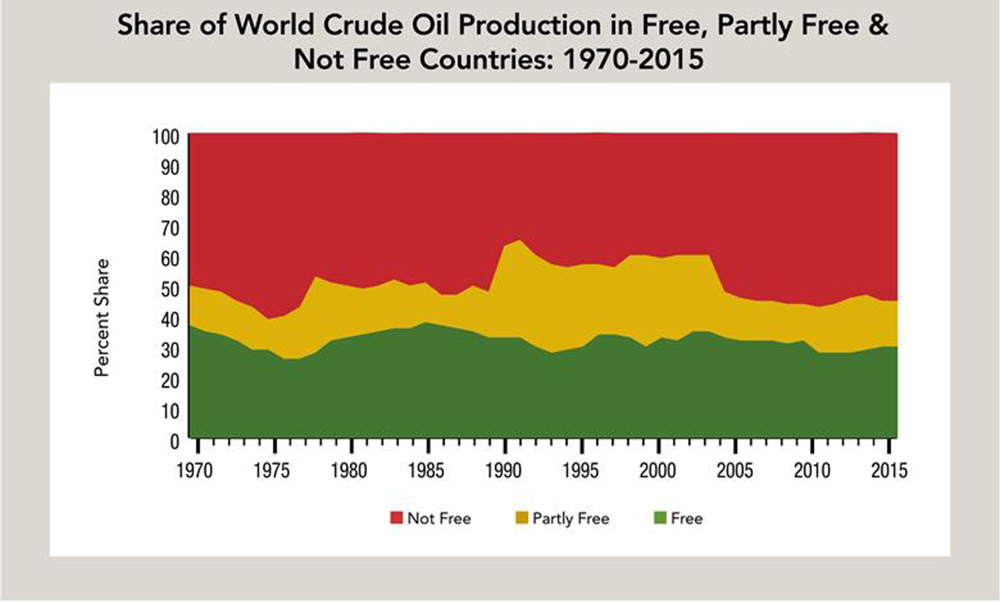

Using production data from Freedom House and the U.S. Energy Information Administration, we are able to calculate the share of crude oil is produced in Free, Partly Free, and Not Free countries and how the share of each has changed over time. It’s not a pretty picture.

The chart nearby shows the historical trends in the share of global crude oil production from Free, Partly Free, and Not Free countries, and it confirms that Mr. Priebus was spot on.

- Since 1970, typically 50% to 60% of the world’s current oil has originated from Not Free countries (it was about 55% in 2015).

- Partly Free countries produce typically about 10% of the world’s oil. (The break-up of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, when Russia moved from the Not Free to the Partly Free column, is clearly seen. So is Russia’s reversion to Not Free column around 2004.)

- When added together, share of global output from Not Free and Partly Free countries since 1970 has moved within a range of 60% to 70%.

- That means anywhere from 30% to just 40% of world crude oil production has occurred in Free countries. In 2015, it was about one-third and would have been much less were it not for surging oil production here in the United States and in Canada offsetting declines in other Free countries like the United kingdom and Norway.

That’s the precarious world that multinational oil companies must navigate on behalf of their shareholders and their customers every day. Add on top of this the myriad regulatory, geological, climatic, infrastructure, socio-economic, cultural, market, and countless other challenges that companies contend with on a daily basis, and it’s nothing short of remarkable that these companies are able to deliver a product we all need at an affordable price.